What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843-1999

The New Woman: 1920-1935

by Carole Naggar

The interwar period from 1920 to 1935, with its social, economic and political upheavals, was ripe for cultural change. On the technical level, lightweight, speedy and easy-to-use 35mm cameras such as the Leica and the enhancement of photogravure, which made printing easier and allowed the combination of image and text on the same page, were key factors in the realm of the photobook. Also important were cultural exchanges between the Soviet Union and Western Europe, the distribution of illustrated magazines and interactions between writers and artists at numerous cultural congresses. In this context, the modern photobook took shape and flourished as an experimental field for various artistic movements from Pictorialism to Dada, Surrealism, New Objectivity and Modernism.

By the 1920s, women had achieved a measure of independence and began to challenge gender roles, thus increasing their presence in the public arena. More women attended college, becoming lawyers, doctors, journalists and professors, although these privileges were open only to the white middle and upper classes. Women’s photobooks, mostly produced in Europe and the United States, reflected women’s move from the private to the public sphere. However, few women considered themselves authors, and the number of photobooks produced by women during this period does not accurately reflect their growing professional presence.

Photographically illustrated books, scrapbooks, family albums and portfolios can be seen as “proto-forms” from which photobooks evolved from private to public. Like watercolor or embroidery, assembling scrapbooks and family albums was a traditional activity for women with “time on their hands” for domestic tasks deemed non-essential. Julia Margaret Cameron’s albums from the 1860s are prime examples of the way photobooks emerged from the private, single-copy album dedicated to a specific person. She assembled lavishly bound albums with handwritten captions for her sitters, friends and acquaintances, many of them eminent personalities from her privileged social circle.[1] Like Cameron, Doris Ulmann’s A Portrait Gallery of American Editors (1925) possesses a tactile quality characteristic of a family album and her pictorialist training was at Clarence White’s School of Photography, the first professional photography school to grant access to women. As a proponent of Pictorialism, Ulmann sought to demonstrate that photography should be considered fine art, and sequenced her book to be a “gallery” evocative of exclusive clubs where paintings of board members and founders graced the walls.

An assistant of Gertrude Käsebier and a fellow of Alfred Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession—which, like Pictorialism, promoted photography as a fine art medium—Alice Boughton was one of several New York women who ran their own studios starting in the 1880s. With Käsebier, Zaida Ben-Yusuf, Mary Devens, Emma Justine Farnsworth, Clara Sipprell, Eva Watson-Schütze and Mathilde Weil, Boughton was part of a group of prominent women photographers at the turn of the century. Art, politics and gender equality were woven into her work as a socialist and feminist active in the New Woman movement—a term popularized by Henry James, one of Boughton’s sitters. Reflecting their growing presence in the artistic community, eleven of the twenty-eight portraits represented in Boughton’s later book, Photographing the Famous (1928), are of women. Rejecting posed portraits in favor of captured movements, her photographs present models from outside her privileged social circle and explore extremes in tonality—shades of white on white or black on black.

1933 Hannah Höch Album

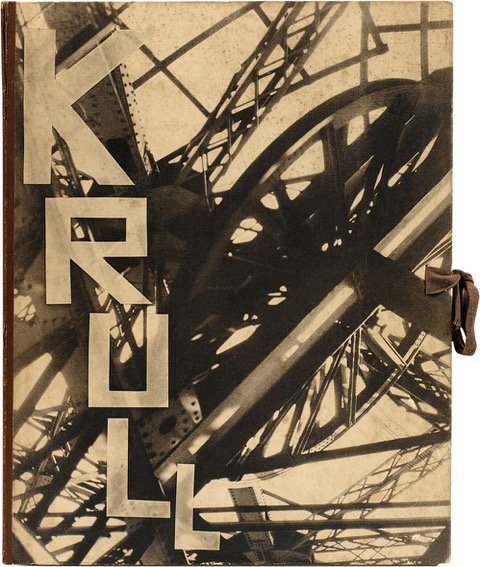

Paris emerged in the 1920s as a center of avant-garde art and a refuge for many expatriates and exiled photographers from elsewhere in Europe and the United States. With the explosion of construction, industry and technical innovation, a Machine Age aesthetic flourished and was reflected in imagery in the fields of photography and advertising. A proponent of this artistic sensibility, Germaine Krull was strongly influenced by her friends Robert and Sonia Delaunay’s school of Orphic Cubism and its fascination with urban subjects and modern industry. Taking her cue from Russian avant-garde movements, Krull created Métal (1928), an unbound book with an angled, hand-lettered title inspired by constructivist works by Gustav Klucis and Petr Galadzhev. A shift from Pictorialism to Modernism, the folio’s loose, unpaginated structure and lack of captions invite the reader to arrange the images in any sequence. The result is a “book-space” that Russian artist El Lissitzky had presciently described as an entity that emerges when a reader and book interact.

An inventive rethinking of the book, as realized by Lissitzky and his Russian peers, paved the way for the birth of the modern photobook in the Soviet Union, where it found some of its most remarkable expressions. The confluence of photomontaged images in cinematic sequences with bold colors and dynamic typography became the hallmark of Soviet photobooks. Designer and artist Varvara Stepanova, known for her photomontages and collages, was fascinated with the book as a material object. In 1924, for the stage design of An Evening of the Book—a play that was part of a mass campaign to propagate universal literacy—she created a gigantic book from which heroes of pre-revolutionary and revolutionary volumes stepped out of the pages. Her contribution to Groznyi smekh. Okna Rosta (A Menacing Laughter: The ROSTA Windows, 1932), a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the ROSTA windows, is the endpapers illustrated with a photomontage from repeated and diagonally placed images of a Red Army soldier by Boris Ignatovich on a red background. The montage is accompanied by a quote from “Red Hedgehog,” a poem by the book’s author, Vladimir Mayakovsky.

Olga Linckelmann and Georg Riebicke’s photographs in Hagemann’s Über Körper und Seele der Frau (About Body and the Woman’s Soul, 1927)

The Soviet state publishing houses of the 1920s published brochures and books on a massive scale, using them as propaganda and educational tools. Photography was an essential part of the movement, especially in children’s books such as Egor-Monter (Egor the Electrician, 1928), in which photomontages by Olga and Galina Chichagova of images by Nikolai Zubhov tell the story of an electrician-hero who uses light as a metaphor for knowledge. Women played a significant role in the production of children’s and other photobooks during this period. However, paradoxically, there are few examples of a Soviet woman as the sole author of a photobook. Instead, their contributions were almost always in collaboration—often as husband-and-wife teams such as Stepanova and Aleksandr Rodchenko—with credits usually assigned to the men.

Ulmann’s soft-focus yet realistic examination of the Gullahs’ hard-lived faces and harsh living conditions presents her subjects almost as receding memories brought back from oblivion—a paradox that creates the images’ inner tension.

An American Machine Age aesthetic—with its technological innovations, factory assembly lines, shiny skyscrapers and industrial design, represented in the work of painters like Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth and Georgia O’Keeffe—paralleled that in Europe but without the stylistic extremes of Futurism and Orphic Cubism. Margaret Bourke-White’s Eyes on Russia (1931) documents the quasi-religious machine fervor of the Soviet Union during Stalin’s first five-year plan when the country transitioned from an agricultural society to an industrial center. Unlike her Soviet peers and proponents of Modernism and New Objectivity, Bourke-White seldom used extreme perspectives to showcase Soviet workers as heroes. Instead, she favored a middle view where workers posed mid-movement within carefully lit spaces that included machines. In contrast to Krull’s view of a hallucinatory and fragmented industrial world devoid of human presence, Bourke-White’s photographs relay a harmonious, optimistic collaboration between man and machine—one closer to the American photo-documentary tradition initiated by Lewis Hine.

In Europe, and especially in Germany, the New Woman’s liberation began with a focus on the woman’s body. Inspired by Nacktkultur, an early 20th-century German naturism movement that spawned an extensive network of private clubs and schools, Dr. Bess Mensendieck, one of the first American female physicians, regarded nudism as an aspect of feminism—an idea that would help promote a new, modern identity for women in both the United States and Europe. Along with Alice Bloch and Dora Menzler, Hedwig Hagemann was part of a group that followed and adapted Mensendieck’s teachings. Like psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich, whose therapy advocated the liberation of blocked energy in the body, many women believed that the life of the mind could be enhanced through the senses, with nudity breaking down boundaries between classes and leading to social change. Beyond illustrating gymnastics, Olga Linckelmann and Georg Riebicke’s photographs in Hagemann’s Über Körper und Seele der Frau (About Body and the Woman’s Soul, 1927) evoke the paintings of Arthur Bowen Davies, expressionist dance and Isadora Duncan’s “barefoot modernism.” They also possess more than a hint of homoeroticism, another reminder that the New Woman concept sought to erase gender distinctions.

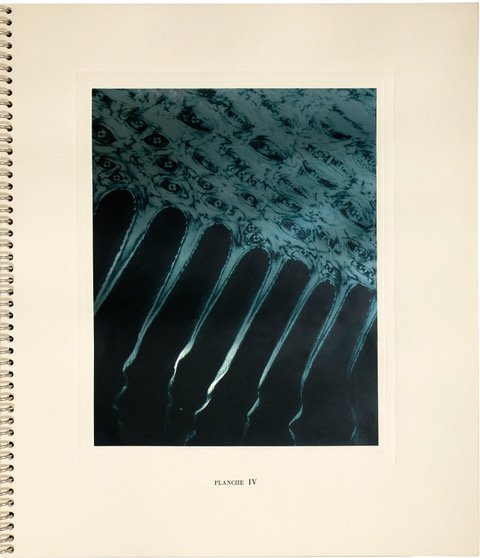

Dr. Albin Guillot Micrographie décorative (Decorative Micrography, 1931

At the release of Doris Ulmann’s Roll, Jordan, Roll (1933), the United States had just emerged from the worst of the Great Depression. In tandem with a text by Julia Peterkin, Ulmann’s photographs of Depression-era African Americans from the Gullah region of South Carolina combine her earlier pictorialist sensibility with a stark, modern documentary style to present portraits as psychological studies. In her chain gang photographs, for instance, the prisoners’ body language and facial expressions convey both their defiance and longing. Ulmann’s soft-focus yet realistic examination of the Gullahs’ hard-lived faces and harsh living conditions presents her subjects almost as receding memories brought back from oblivion—a paradox that creates the images’ inner tension. While photographs taken in the South by Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographers Marion Post Wolcott and Dorothea Lange were intent on changing public attitudes by depicting the plight of the underprivileged, Ulmann’s images, done four years earlier, did not necessarily have a social justice agenda. Rather than seeking material help, the Gullahs portrayed by Ulmann seem only to ask for recognition.

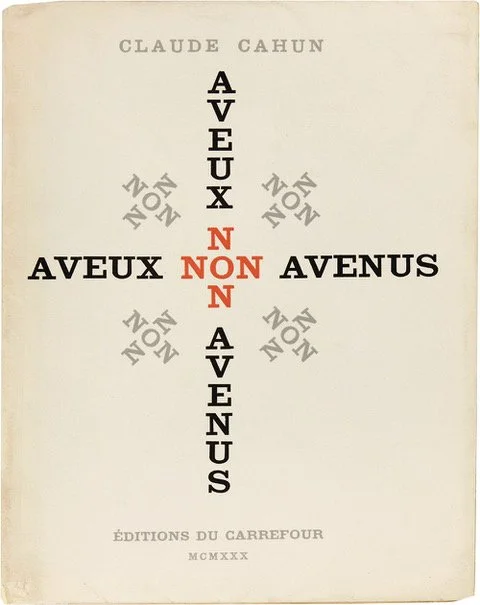

While Errell and Thorbecke’s books looked outward to other cultures, Aveux non avenus (Disavowals, 1930) by surrealist Claude Cahun looked to the self as a means to explore the limits of gender.

Ellen Kolban Thorbecke (also known as Ellen Catleen) and Lotte Errell’s work, photographed in China and Africa respectively, showcase the emergence of women in the rising fields of photojournalism and ethnographic travel. Working outside Europe provided these self-taught photographers a sense of liberation from Western social constraints, politics and customs. Both were gifted authors and photographers who wrote documentary texts and used Rolleiflex cameras to shoot pictures for photobooks that created a “word and picture” form parallel to the photo-essays published in avant-garde European magazines such as AIZ, Vu and Regards.

Errell was among many European Jewish women in the Weimar Republic who pursued a career in photography, one of the few fields accessible to women without academic credentials. Similar to the extraordinary Swiss photographer and writer Ella Maillart—whose publications include Des monts Célestes aux sables Rouges (From the Celestial Mountains to the Red Sands, 1934) and Oasis interdites (Forbidden Journey, 1937)—Errell became interested in ethnological reportage and published Kleine Reise zu schwarzen Menschen (A Little Journey to Black People, 1931) after traveling to Ghana in 1928. During the early 1930s, a period of “East Meets West,”[2] China was a frequent topic for western writers, filmmakers and artists such as Pearl Buck, Josef Von Sternberg and André Malraux, as well as Thorbecke, whose Peking Studies (1934) and People of China (1935) are a mix of travel diary and social documentary. Unlike professional anthropologists, they did not look for systems or types but focused on individual people and the details of their lives. Errell’s close-up photographs of women and children and Thorbecke’s portraits of Chinese people in all walks of life use a straightforward documentary approach, at times colored by a colonialist perspective and the aesthetics of the New Vision..

While Errell and Thorbecke’s books looked outward to other cultures, Aveux non avenus (Disavowals, 1930) by surrealist Claude Cahun looked to the self as a means to explore the limits of gender. Created with her lover and stepsister Marcel Moore some sixty years before Cindy Sherman, Aveux non avenus is the first photobook in which an artist stages a theater of the self. To embody different incarnations—female, male and androgynous—of what Cahun believed to be the unknowable self, she created self-portraits that purposefully blur all gender markers. Photomontages and overprints of a costumed Cahun are mixed with disassociated fragments of texts to create a hybrid third dimension, exemplified in her surrealist collages of constellation-like body parts floating on a black background.

To embody different incarnations—female, male and androgynous—of what Cahun believed to be the unknowable self, she created self-portraits that purposefully blur all gender markers. Photomontages and overprints of a costumed Cahun are mixed with disassociated fragments of texts to create a hybrid third dimension, exemplified in her surrealist collages of constellation-like body parts floating on a black background.

Like surrealist photographer-filmmaker Jean Painlevé, who exhibited biological artifacts with his images of underwater fauna, Laure Albin-Guillot was part of a group that brought scientific images into the artistic realm. With her husband, Dr. Albin Guillot, she amassed a collection of micrographic specimens: crystallizations, plant cells and animal organisms. In her Micrographie décorative (Decorative Micrography, 1931), the microscopic becomes immense, as in an image of nitric acid that looks like forest foliage. Her microphotographs posit that close observation of nature and understanding of natural phenomena are as powerful as imagination, and can bring a poetic universe to life. Linking New Objectivity with Surrealism, the images hint at a secret organization of the world, where animal, vegetable and mineral become one.

Aënne Biermann, an amateur mineralogist, is another example of a woman photographer whose early work found inspiration in scientific specimens from the natural world. A self-taught Jewish photographer associated with the New Objectivity movement in the Weimar Republic, she gained a degree of success with the inclusion of her photographs in exhibitions such as Film und Foto (1929-1930). In Aënne Biermann: 60 Fotos (Aënne Biermann: 60 Photographs, 1930), a monograph she published under the Fototek series conceived by Franz Roh and Jan Tschichold, she pairs straight photographs in a binary design that would become prominent in photobooks. The book’s cover shows a child’s hand and a page of his writing: a German-English translation of everyday words. Is it to suggest that photography itself is a translation of the world accessible through reading? Or did photography itself, as László Moholy-Nagy wrote, become the new writing?[3] Photographers such as Biermann, Lucia Moholy and Gertrude Arndt created on equal terms with men during the Weimar years. Yet history has not always properly credited their creations, with much of their work largely unrecognized until recent years. It was only in the 1960s that Lucia Moholy, for instance, recovered the negatives she had loaned to Walter Gropius and that he used for years without her permission and credit.

Kleine Reise zu schwarzen Menschen (A Little Journey to Black People, 1931)

Claude Cahun Aveux Non Avenus 1930

In the early 1930s, as the Nazi Party began to assert its opposition to the avant-garde that flourished in Germany during the Weimar period—climaxing in Munich in 1937 with the Degenerate Art exhibition—collagist Hannah Höch, who was one of the only women involved in the male milieu of the Berlin Dada movement, retreated from active artistic life to her suburban house. While there, she conceived and worked on Sammelalbum (Album, 1933), a personal and eccentric archive of images culled mainly from women’s magazines. Although a redefinition of women’s roles had taken place during the Weimar years, Höch was aware that liberation had not translated into equality and that stereotypes generated by the print media represented women as objects and subjects, commodities and customers. The album shows her desire for both order and ambiguity within a world on the verge of exploding into the chaos of the Second World War.

Although a redefinition of women’s roles had taken place during the Weimar years, Höch was aware that liberation had not translated into equality and that stereotypes generated by the print media represented women as objects and subjects, commodities and customers. The album shows her desire for both order and ambiguity within a world on the verge of exploding into the chaos of the Second World War.

Margaret Bourke White Eyes on Russia 1931

To suppress the growing number of openly sexual and independent women working outside of the home, Adolf Hitler denounced the “emancipation of women” slogan, declaring it an invention of Jewish intellectuals and those associated with Marxism.[4] He asserted, “There is nothing nobler for a woman than to be the mother of the sons and daughters of the people.”[5] The Nazis made great use of visuals through posters and picture books to instill a message of motherhood as the ultimate expression of womanhood. Mutter und Kind (Mother and Child, 1930) by Hedda Walther, whose early work was included in Bauhaus and modernist exhibitions such as Film und Foto, is an interesting case of a photobook with somewhat ambiguous politics. With its reverence for the sentimental and interest in animals, the book suggests that children and animals are primitive beings, and it alludes to Nazi ideological tenets of a woman’s innate role as a mother. By 1936, political ambiguity was gone, and Walther was an outright Nazi sympathizer, publishing photographs of sanctioned “types”—such as a Lower Saxony farmer couple in costume—in the magazines Deutsche Meisteraufnahmen, Signal and Die Dame.

A major task of the Nazi Party Office of Racial Policy was to produce propaganda materials promoting their views on race. In that context, photography became a powerful political weapon. Beyond its use in racial science, the medium was soon used to produce a nostalgic nationalism as seen in the work of Erna Lendvai-Dircksen, who, through her portraits of rural dwellers in Das deutsche Volksgesicht (The Face of the German People, 1932), sought to express an authentic essence of the German national identity. In an essay she wrote for Das deutsche Lichtbild (The German Photograph, 1931),[6] she strongly opposed the New Objectivity movement, which she called “a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” and warned about “foreign style mixes” that betrayed national purity. Eugenics was an extreme but logical outcome of this ideological position, and Lendvai-Dircksen was soon recruited to be the primary photographer for the Nazi eugenic journal Volk und Rasse (People and Race). By contrast, Lotte Errell and other professional photographers, whose pictures might challenge the visual mandates of the Nazis, were driven out of the country.

The surge in the number of women’s photobooks from 1920 to 1935 was mostly limited to select parts of Europe—France, England, Germany and the Soviet Union—as well as the United States, and to white women privileged either by their social status (and often whom they were married to) or by belonging to an artistic movement or school such as the Bauhaus, Dada, New Objectivity, Pictorialism and Surrealism. While women did make big strides in the profession, being a photographer didn’t always translate into asserting oneself as the sole author of a book. And with change proceeding at a much slower pace in other parts of the world, several more years would pass before photobooks by women emerged from continents other than North America and Europe.

AUTHOR’s BIO

CAROLE NAGGAR is a writer, poet and photography historian based in New York and Paris. She has written numerous books including the first Dictionnaire des photographes (Dictionary of Photographers, 1982), as well as essays for numerous catalogues, newspapers and magazines. Among her recent and upcoming publications are 70 Years of Correspondences: Picto and Magnum Photos (2020), Magnum Photobooks (co-author with Fred Ritchin, 2017), Giacometti à la fenêtre (Giacometti at the Window, 2019), Tereska and Her Photographer: A Story (2019) and The Many Lives of Chim (2022).

ENDNOTES

[1] For instance, Cameron’s Watts Album (1864), Herschel Album (1864), Thackeray Album (1865), The Tennyson Album (1874) and Norman Album (1862).

[2] For an in-depth discussion of the “East Meets West” concept, see Rik Suermondt, “Ellen Thorbecke,” PhotoLexicon, vol. 16, no. 32 (November 1999).

[3] “The illiterate of the future will be the person ignorant of camera and pen alike.” Lazlo Moholy-Nagy quoted by Louis Kaplan in Moholy Nagy: Biographical Writings, (Chapel Hill, NC: Duke University Press, 1995), 36.

[4] Adolf Hitler (speech, National Socialist Women’s League, Nuremberg, 8 September 1934).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Das deutsche Lichtbild, Jahresschau 1931 (Berlin: Verlag Robert & Bruno Schultz, 1931).v