Cuentos de Cuarentena | Quarantine Tales

by Lexi Parra from Caracas, Venezuela

“Vivimos en una zona de guerra.”

We live in a war zone.

Taken from a much longer conversation I had last week with a friend about the situation in her neighborhood. During the past months of quarantine, her beloved barrio has been overtaken by police searching for the malandros (gang members) who run the area. Grenades, checkpoints, mass arrests and intimidation are part of daily life for now.

It comes in waves, but never really goes away, she said - reflecting on her experiences living there as a young kid and now a working mother.

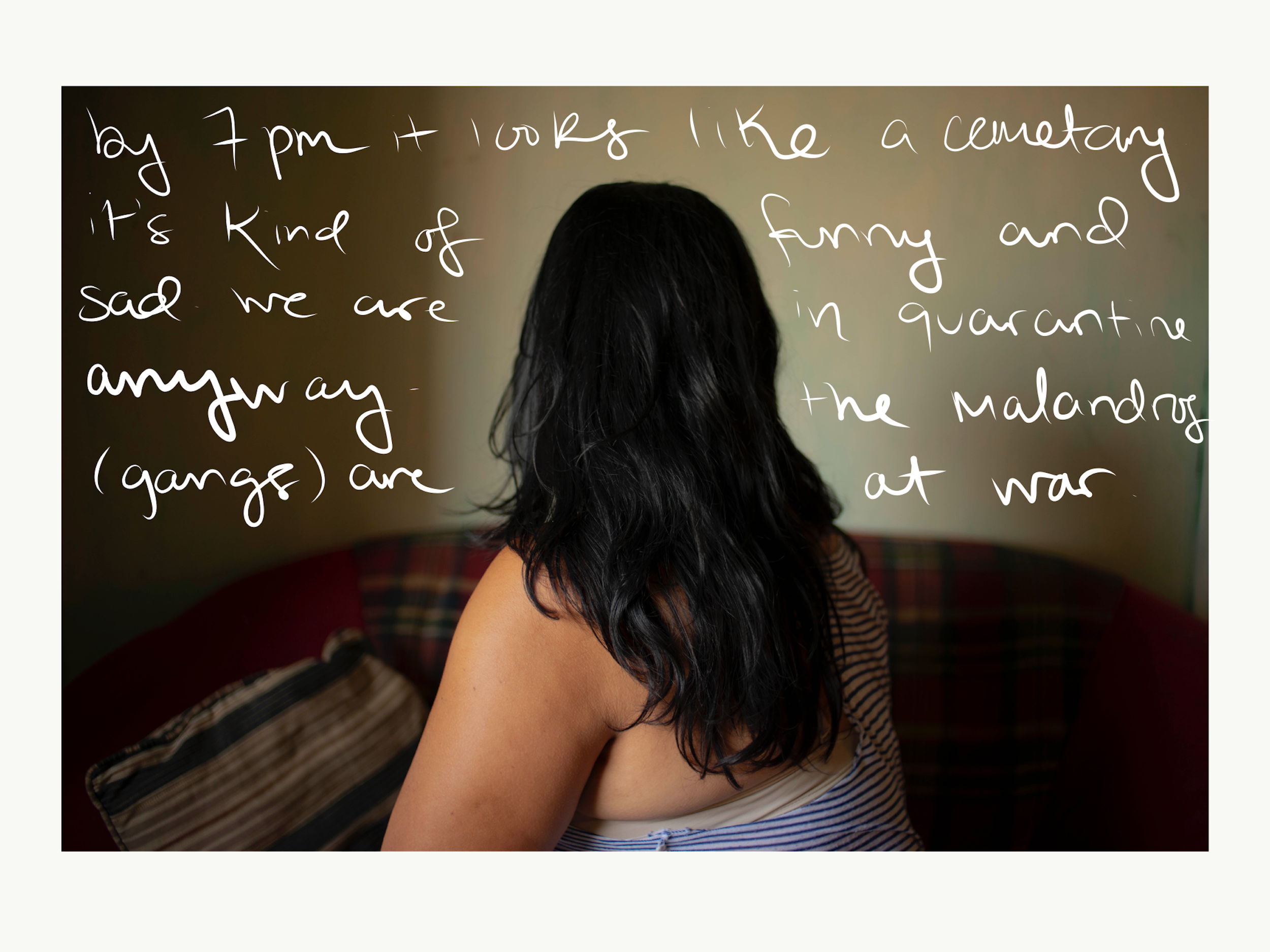

Double exposure experiment inspired by this conversation..

Pamela’s home somehow always becomes my refuge. Over a year ago, I spent three days holed up in her apartment - bedsheets on her living room floor and a bottle of tequila got us through the nights of gunshots, fires and guarimba / FAES (protests / security forces) disaster.

Now for my first visit out of the house in two months, that makeshift bed on the ground became my haven once again.

The next morning we put on some music, made coffee and enjoyed the beautiful morning light that comes through her apartment windows. Down below, there were the comforting sounds of the street and people setting up for the day. Although, due to the quarantine, the streets will be emptied out by mid afternoon.

A friend asks, “Did you hear the grenade?”

I answered, “I heard something...but the music is on, I couldn't tell what it was.”

My friend responds, “It came from the barrio, but like right up there.”

Inside, Pam’s home may be my home away from home.

Outside a war continues on.

“Marica no sé, no creo que en el largo plazo es una solución: otra fuerza. No sé. No sé.”Girl, I don’t know, I don’t think this is a long-term solution: another force. I don’t know, I just don’t.

In El Setenta, the malandros (gangs) have fled. Since the beginning of the quarantine, the police have taken control. What started as chaos has settled down and become the new normal. But can it be trusted?

A friend (unidentified) reflects that 25 years ago, the gangs had respect. Sure they had their drug businesses, but if there was a conflict, they held a trial. They provided security and respected the residents of their territory - so much so that people could sleep with their doors open. Then, a few years ago ‘la limpieza’ (the state-sanctioned mass killings of gang members) ended this era. Young boys with guns and ambition took over the zone and didn’t show respect or have any clear rules. “I don’t look at people anymore - you don’t know who is who. I walk straight to my house, that’s it.”

Since the police have taken over and the new gang has fled, hiding out, the residents have had serious consequences. The police stopped the arrival of the CLAP (government subsidized food boxes), saying that those distributing the boxes [elderly women from the neighborhood] were affiliated with the gangs. The people suffered severe food insecurity because of where they live and forces beyond their control.

What do you do? Where do you place the blame? The hope?

Video in Pamela’s apartment, in El Valle - at the entrance of the road to El Setenta. Text from a friend, venting about their worries, what the future will hold.

“Por la comida,el presidente dice que cada 15 días está llegando la caja pero eso es mentira. Aquí muchas personas me han ayudado, regalando comida o algo para aguantar.”

Regarding the food, the president says that every 15 days the boxes [of subsidized food, CLAP] arrive, but it’s a lie. Here many people have helped me, gifting me food here and there to get by.

Deisy and I talk almost every day, now more than before the quarantine. She loves gossip and I love the distraction. Her situation is difficult - yet she is always kind, cracking a joke. Honestly, you wouldn’t know that she is the sole income for her family right now or that she spends her spare time taking care of her husband who has pancreatic cancer … because she doesn’t let that show.

Instead, when we talk, she whips out her phone and shows me pictures she took over the weekend. That’s when I see the other side of Deisy: dressed up in tight mini dresses and snapbacks, with a sassy pose showing off her cuerpito (body). “That was after a few drinks, ya know? Have to have fun sometimes too,” she laughed.

"I'm sorry love, just calling to say hi. And talk about some shitty things that have been going on - I wanted to vent, I hope you're well. And sorry, I know it's late."

15 April 2020

A dear friend called. We were able to talk the next morning. Normally we see each other every week, but since the quarantine started over a month ago, I've been stuck on the other side of town. My friend lives in a barrio near where we both often work. He let it all out: the gang killed a cop, now the state forces are seeking revenge. Innocent people have died. He walks to work, at least a few times a week, despite the quarantine. No buses or motos are allowed to pass. There are checkpoints. It's risky. The virus is just the newest of a long list of threats...He says, "There's no breath. No time to rest, or process." After he exhales the anxiety that has been building up, I offer love and support that doesn't feel at all helpful or enough, but I try. He tells me about the pillowcases and blankets he is sewing. "I found my talent," he jokes. The colors, textures, using his hands - it's a welcome distraction.

“La situación del pobre, la situación de quien trabaja - no los ven. Tu ves nada mas de lo que te conviene. Ellos no se meten en el barrio para ver la realidad de verdad. No les conviene entender.”

The situation of the poor, of those who work - they don’t see it. You don’t see something when it isn’t convenient. They don’t go into the barrio to understand the true reality. It isn’t convenient for them to understand.

Deisy has a no-nonsense attitude. But whenever I go to sit in the garden, she is always ready to chat or hablar paja. A welcome relief - especially during these times of quarantine. Under these new circumstances, she wasn’t sure if she was going to be able to continue to work, but thanks to a favor from a friend she can now move freely to and from her home in Petare. .

With this salvo-conducto (travel pass) she is able to ride the subway a part of the way to and from the apartment building where she is the maintenance worker. “I am the only one with an income in my home right now, so honestly I would walk every day if I had to. Sometimes, because the jeeps don’t always run, I do. Poco a poco (Little by little).” .

She takes great pride in having an ‘honest job’ (her words) to provide for her home. While her oldest sons are grown, she has a husband with pancreatic cancer and a 15 year old teenager at home. “Gracias a dios nunca nos hace falta.” (Thank god, we never go without.) .

In a country with extreme political polarization, living between the contrast of a barrio that is currently dealing with gang wars and heavy police presence and working in an upper class apartment building, Deisy doesn’t concern herself with anything that is outside of her own control.

“Yo no soy ni del uno ni del otro. Si no trabajo, no como. Qué vale mi opinión si todo va a seguir igual?”

I am neither on one side or another. If I don’t work, I don’t eat. What is my opinion worth when things always stay the same?

“Hola mi vida…estoy en el trabajo, baje antes de que los pacos subieran. Están allá ahorita, subieron ayer también y hicieron desastres…quemaron dos casas y además explotaron una con una granada… hoy están devuelta con el operativo otra vez. Y obvio estoy angustiado por mi familia que esta allá arribe aún.”

Hello my love, I’m at work - came down before the cops went up. They are up there right now, they went up yesterday and made a mess … they burned two houses and even exploded one with a grenade … today they are back with the operative again. And obviously I’m worried about my family who’s still up there…

Over the weekend, I checked in with a friend. This was the update they gave me. As far as I know, their family is still okay - but the state forces have not completed their operative, so they continue to go up into the barrio, a constant threat to everyone - involved or innocent - until they find what/who they are looking for.

Since knowing about this situation my friends are dealing with in their neighborhood, the physical distance has felt immense. Normally, we all go to work and share that safe space - we can vent, forget the stresses of the Caracas streets, and be there for each other. Now, that emotional space is gone. We use WhatsApp and phone calls to make up for it, but that digital connection only goes so far.

This video is a reaction to this distance, the contrast between what I see outside my window and what I read or hear from friends just on the other side of town. How is it that at the same time as I feel numbed by the silence of my neighborhood’s streets friends are dealing with chaos, a stress they can’t shake, just a short moto ride away?

Gloria runs a kiosk by my house and every time I have gone to the supermarket during quarantine, I have a coffee and chat for a minute. Her crazy stories and infectious laugh help me to step out of the ‘lucha’ and just joke around. Since quarantine has started, as police are constantly circling the neighborhood and forcing informal businesses like Gloria’s to close - despite legally being allowed to stay open, she has been struggling to pass the time. So, she started writing a book about all the characters and stories that happen or are re-told at the kiosk. Sometimes, when I stop by she shares a new chapter or character she is working on.

Despite the uncertainty of the country, of COVID-19 and economic woes, despite whatever overwhelming thing people may be facing right now, I am in awe of Gloria’s unwavering smile and good spirit. She reminds me of the beauty - and necessity - of the lessons I am learning in Venezuela: how to resolver (or deal with something), chalequear (joke around) and just enjoy the moments that we can - a pesar de todo (despite everything).

audio translation /english: " Ah what about the food, if the prices go up or down, what if the dollar ... I'm in the same place as everyone else [ with these worries ]. I have been able to find tranquility in the middle of such a storm. We have learned how to be partners, as partners pushing on with what is the most important thing in my life...my son. To take Alan and fill him with love after living through a destructive situation for many years - Alan and I. Leonardo has been a fundamental piece so that we [ my son and I ] can move on, understand, learn to accept love, care..."

This is a piece of audio from a voice message sent by a friend earlier this week. She has fought for everything in her life - an unparalleled strength inside such a flaquita - which is why it isn't surprising that a global pandemic isnt cause for much more stress than anything else that could happen. Our friendship reached a deeper level when we were able to connect over past traumas. She has since left the person who had often left her with marks, scared for her well being. She has found strength in accepting help and real love from those around her. .

Now, while constant police raids have made going home dangerous during the quarantine, she reflects on feeling grateful to be able to stay with her new partner in his neighborhood, a silver lining: getting to spend time with someone who shows her and her son the love and patience they both deserve. The virus barely comes up in our recent calls and messages - there seem to be more pressing worries as well as little joys to talk about.

Diptych L: My hand holding my phone, with our conversation thread open. R: Her hand reaching for flowers outside her home, during a visit last year.

A reaction to the fact that, for now, our connection lives on Whatsapp.

“Esta situación se ha salido de las manos...Y con este tema de la gasolina, de pana no se que vamos a hacer...como ya, ya. Me pongo a pensar en el futuro de mi hijo. Si eso va a seguir así o se va a ser para siempre, mi hijo no tiene futuro aquí.”

The situation has gotten out of hand - and now with the issue of gasoline, for real I don’t know what we are going to do...it' s like enough, enough. I find myself thinking about my son 's future. If things continue like this or go on forever, my son doesn’t have a future here.

Julieth is a professional home nurse, currently working in a building in El Cafetal caring for her long-term patient, Sra. Carmen. Julieth is kind, timid but level-headed. After learning a bit more about her life, I saw how a 22 year old came to carry herself with such assurance. She has to. In a country dealing with simultaneous crises, women are often the ones holding things together. Julieth is no different.

She travels from Guatire every few days for 72 hour shifts at Sra Carmen’s apartment - splitting the week with her sister-in-law. Despite the grueling commute - sometimes over four hours waiting for a bus - she says, “It is what it is. You have to find a way to get here - cause you have to work...”

When she isn’t taking care of Sra Carmen, she is spending time with her one year old son and helping take care of her home, which she shares with her husband’s family. All of the women in the house are working nurses, too. During the past months of quarantine, Julieth says she is grateful to be working for an at-home patient after seeing her mother-in-law dealing with direct COVID-19 exposure every day at a public hospital, El Llanito. Julieth adds “It’s stressful because she has 8 grandchildren at home, so we are always doing what we can to make sure she protects herself. But where else is she going to stay, ya know?” Julieth adds that there is no PPE at that hospital with every worker doing what they can to “resolver” (make it work), a concept that has seeped into every part of daily life. “To work in the healthcare industry today, you have to want it because it is “arrecho” (brutal.)

“No, de qué verdad, uno hace milagros - para vivir, para sobrevivir, para salir y llegar sana a su casa. Milagros. Osea…uno vive al gracias de dios porque el dinero no te alcanza, porque las inseguridades están - uno no sabe dónde te puede atacar cualquier situación.”

No, seriously, people make miracles happen - to live, to survive, to leave and come home healthy. Miracles. I mean, people live by God’s grace … because the money doesn’t last, because the insecurities are there - you don’t know when you could get attacked by any situation.

It was a hot Sunday afternoon in Guarenas, a commuter city outside of Caracas. A soft breeze was coming in through the large window of the living room. The apartment was filled with home-y sounds: little kids giggling, LEGOs hitting the concrete floor, chatter between sisters on money transfers, the coming and going of neighbors with groceries, water from the building’s tank...just a regular Sunday to prepare for another long week.

Julieth lives with her husband’s family where all the women are working nurses and care-takers. Due to COVID-19 and the strict quarantine, they are currently taking 3-5 day shifts and work out schedules so that on their days off, there is at least one of them at home to take care of the kids.

Julieth’s mother-in-law is the matriarch of the family + currently a nurse in the ICU of El Llanito, a public hospital in Caracas. If she isn’t at the hospital, she is taking care of her sweet, energetic grandchildren or working with the government’s efforts providing health care and testing for citizens of the barrios, lower-income neighborhoods. Her audio is paired with Julieth’s moving portrait here because her dedication to public health is what inspired Julieth to become a nurse.

Despite the stress of exposure to COVID-19, the women of Julieth’s family are grateful to be working and for the ability to lean on each other when it comes to keeping everything smooth at home.

"By 7 pm, it looks like a cemetery. It's kind of funny and sad - we are in quarantine anyway. The malandros [gangs] are at war."

A las 7, ya es como un cementerio. Es medio cómico, y triste - ya nos estamos resguardando en la casa. Los malandros nos han caído encima.

My friend, a joyous strong woman, told me about the gang war in her neighborhood as if it was just another fact. She told me about it with a dark humor that only a Venezuelan could. She goes to work and, sure, she's nervous about the virus. But the more immediate threat: the groups of sixty guys patrolling her area, armed with big rifles. Her neighborhood isn’t controlled by anyone, so its prime territory. She moved on to talk about the rosary prayers she was doing with her neighbors - to pray for health, for her family and for Venezuela to come out of this okay.

“The hell continues. We are still in the struggle.”

A friend messaged this to me. Just this. After a few minutes, he gave me more to go off of - recounting that the police had stopped him on his way home - his saving grace being a flimsy work permission slip proving he wasn’t a malandro (gang member). After getting home, the police were invading a neighbor’s house - he had worked so hard to find a moto, spent a good amount of his day’s pay on the ride, dealt with the cops...all to get home and feel more anxious than he did at work.

Before he told me what was going on, that first message was it. Simple, a statement of fact...but also so much more raw than that. Here, people often say “aqui en la lucha,” or “here in the fight” when you ask them about their day. It’s a way of saying “I’m good, considering.” or “I’m out here, you know...”

Fight, struggle … These words describe everyday life. Now, we find ourselves in a global pandemic, in a country with bountiful oil reserves and days-long lines for gas, in a city struck with street gangs and gangs in uniform … so the struggle continues, yes ...

The struggle continues while I sit on a bench in my apartment building, looking up at the fiery sky. The struggle comes in through texts, calls and moments of venting that allow friends to let it out + me to feel closer to them, despite the weeks of distance. Here life is magical, as well as full of real struggle. People are what get you through: to me, that’s a big part of the magic.

So this video is a reaction to this new distance, a distance that almost feels antithetical to daily life here...a reaction to the contrast between what I see outside my window and what I read or hear from friends just on the other side of town.

“I have this feeling that the barrios end up being like prisons...they limit you so much that you aren’t allowed to dream. I love my barrio but you find yourself between a rock and a hard place.

When the police took over, they controlled the area a lot - I won't deny it - but they murdered innocent people. So that is the price that we have to pay in order to have the possibility of being somewhat ‘calm.’ They come up with the bias that we are all gang members. Everyone, ya know, believes the people who live in the barrio just aren’t worth anything …

So I always ask myself this question: is it true? Are the only opportunities outside the barrio or not? Are we able to create our own, someday?”

This is an ongoing thought, question, process to share the struggle, beauty, violence and resilience that lives within a notorious barrio of Caracas. A place my friends call home. A place that is, in many ways, unphotograph-able and talked about in vague terms only. A friend shared the internal conflict of loving home and also feeling trapped within it.

Double exposure: Hand of a friend on the wall of her home. A papagayo (kite) flying over her neighborhood on a clear afternoon.