Cathy at war

Cathy at War is a documentary film by Jacques Menasche about Catherine Leroy, a pioneering conflict photographer of the Vietnam War. The film portrays Leroy’s experience in Vietnam through a meditative montage of still images narrated by her journals and letters she wrote to her parents, featuring interviews with David Douglas Duncan, Don McCullin, Horst Faas and others. Leroy’s photographs have been on the covers of Life, Time and Look, and awarded the Capa Gold Medal and the George Polk Award, yet today, fifteen years after her death, she remains largely unknown.

In this feature we present a segment of the film, Catherine’s photography, and an interview with the director about his process of making the documentary.

A great film… the power of the film is captivating and, as if it all just happened yesterday, the film is topical and seems to be happening today. This film must be seen, everywhere, in France as in America, in schools of journalism as well as for an audience curious to discover a character so modern, so ahead of her time, courageous, too.

– Raymond Depardon on Cathy at War

FOTODEMIC: What’s your connection to Catherine Leroy? Did you ever meet her?

Jacques Menasche: I met her near the end of her life. She was desperately working on a project trying to put together a photography exhibition at the Vietnam Memorial in Washington D.C. But this was in the years after September 11th and she was having big problems getting that accomplished. She had an ally in Senator John McCain, who had written the introduction for the book of war photography from Vietnam that she had assembled, Under Fire —but even McCain couldn’t do anything at that time, because of, as Catherine put it, fucking ohm-land security.

That exhibition was going nowhere and she was very frustrated. At the time I was the Director of Special Projects at Contact Press Images, and she would come by the Contact office in New York, and she was looking for assistance to get this show happening. That was her sole focus and she was tenacious.

One night we went out together with a group of people to see a film by Raymond Depardon at Lincoln Center. It was a gusty rainy night, and we were crossing Broadway and she had an umbrella and it was like Mary Poppins. She was so small and so thin at that point, she was battling with this umbrella, being lifted off her feet with the wind, pulled across the street. She would come into the office, and she was small yet everyone would be afraid of her, everyone would hide, because once she came in you knew you would have to start working for her.

I don’t know why that was, because at that point, except among some of the older photographers at the agency, her photography wasn’t that well known. Her photography wasn’t known in the 1990s and early 2000s, but she had a way about her of authority, she had authority.

I’d grown up in the shadow of the Vietnam war, and the week I spent in the office—looking at her contact sheets, staring into the faces of the GIs at Khe Sanh and Hue and other places—plunged me into that conflict, and I never experienced the war in that way.

Têt Offensive, Battle of Hué, February 1968 © Dotation Catherine Leroy

Why did you decide to work on her story?

After she died, Contact ended up with her archive. The president of Contact, Robert Pledge, was very conscious of people’s mortality after Catherine died, and Cornell Capa and other people in the industry died. He would always tell me, “It’s too bad we didn’t interview that person.” I had done a number of films at that point; in 2008, I finished a film called Stoned in Kabul with Stephen Dupont, about heroin addiction in Afghanistan. I was working on a film about a class of elementary school kids near Ground Zero on 9/11 called The Class of 9/11, and I had started working on a film about Olivier Rebbot, a photographer who died after being shot in El Salvador.

So I went to Paris and started creating a video archive of interviews about Catherine Leroy. Sometimes with Pledge, and sometimes alone, I started interviewing people who knew her, finding out about her about her career, her life and what she was like, including Horst Faas who was the head of the AP bureau in Saigon during the war.

I was interested in Vietnam. I had seen a few of Leroy’s pictures in Under Fire and other places and it was always Vernon Wike, the “Corpsman in Anguish” image from Hill 881 that you would see, that and a few others. Then one day I went into the Contact office in Paris, where her archive was being kept in a lot of bankers boxes marked “Leroy” and I spent about a week crawling inside these boxes.

I have to say that up until that point when people in the industry would talk about Catherine Leroy, you’d never get the sense that she was a great photographer. In terms of photography from the war in Vietnam, they spoke about David Douglas Duncan, Philip Jones Griffiths and Vietnam Inc., Larry Burrows and Don Mcculin. They didn’t speak about Leroy. Then I sat down for a week and looked through every image on every contact sheet—a lot of which had never been looked at since it was shot—as well as letters she had written to her parents during the war, and other things like receipts, captions, and a memoir that she had started writing about her experiences during the war — and it was like: holy fuck.

I’d grown up in the shadow of the Vietnam war, and the week I spent in the office—looking at that contact sheets, staring into the faces of the GIs at Khe Sanh and Hue and other places—plunged me into that conflict, and I never experienced the war in that way, and I thought: I can reproduce this sensation for other people. So that’s when that began.

That picture moved around, it was a picture of heroism, of grief and sacrifice. It was part of a narrative of sacrifice which I don’t think changed the trajectory of the war at that time, but it did humanize it. It did bring it home in a visceral way that hadn’t been seen before.

Navy Corpsman Vernon Wike by the side of a mortally injured Marine, Hill 881. April-May 1967 © Dotation Catherine Leroy

Can you talk about her accomplishments, how her work changed the public discourse around the war?

She had a big photographic coup photographing the battle for Hill 881 and making a famous picture of the medic, Vernon Wike, leaning over a fellow marine who had been shot and killed on that hill. That picture moved around, it was a picture of heroism, of grief and sacrifice. It was part of a narrative of sacrifice which I don’t think changed the trajectory of the war at that time, but it did humanize it. It did bring it home in a visceral way that hadn’t been seen before. Then in 1968, during the Tet Offensive, she was captured by the North Vietnamese. Catherine was photographing and speaking with her captors, which ended up on the cover of Life magazine, which would have been seen by millions of people.

And again I think that wasn’t something that changed the trajectory of the war, but humanized the conflict and, this time, in a very particular way, the title that ran in LIFE was “The Enemy Lets Me Take His Picture.” So she was to some degree humanizing the enemy, which is why Don McCullin thought it was amazing the American authorities let her stay in Vietnam.

Rather than telling the story of Catherine Leroy, I want to let Catherine Leroy tell the story of the war. The film needed to be Catherine’s chance to make a film, or to have the film that she might have made.

What was her function at that time vs now?

My sense of it is that Catherine did very well at the beginning of her career. She won the George Polk Award, her work was published. But strangely, after the sixties were over and reputations were formed and legacies were formed around the photographers of the Vietnam War, Catherine Leroy was not included in the list. She was not the person you would read about in books. Not the person that was talked about. After I saw her photographs and made the film I wondered what in the hell had happened. Part of it, I know, is that she was a very difficult person. She insulted the head of the AP, insulted the Macvee in Vietnam. She had cursed out everyone at the agencies and publications, and I think there was a kind of “closing of ranks” in the photographic industry. And she was left on the outside of that. That’s my gut feeling. She was frozen out. That’s why nobody knows who she is.

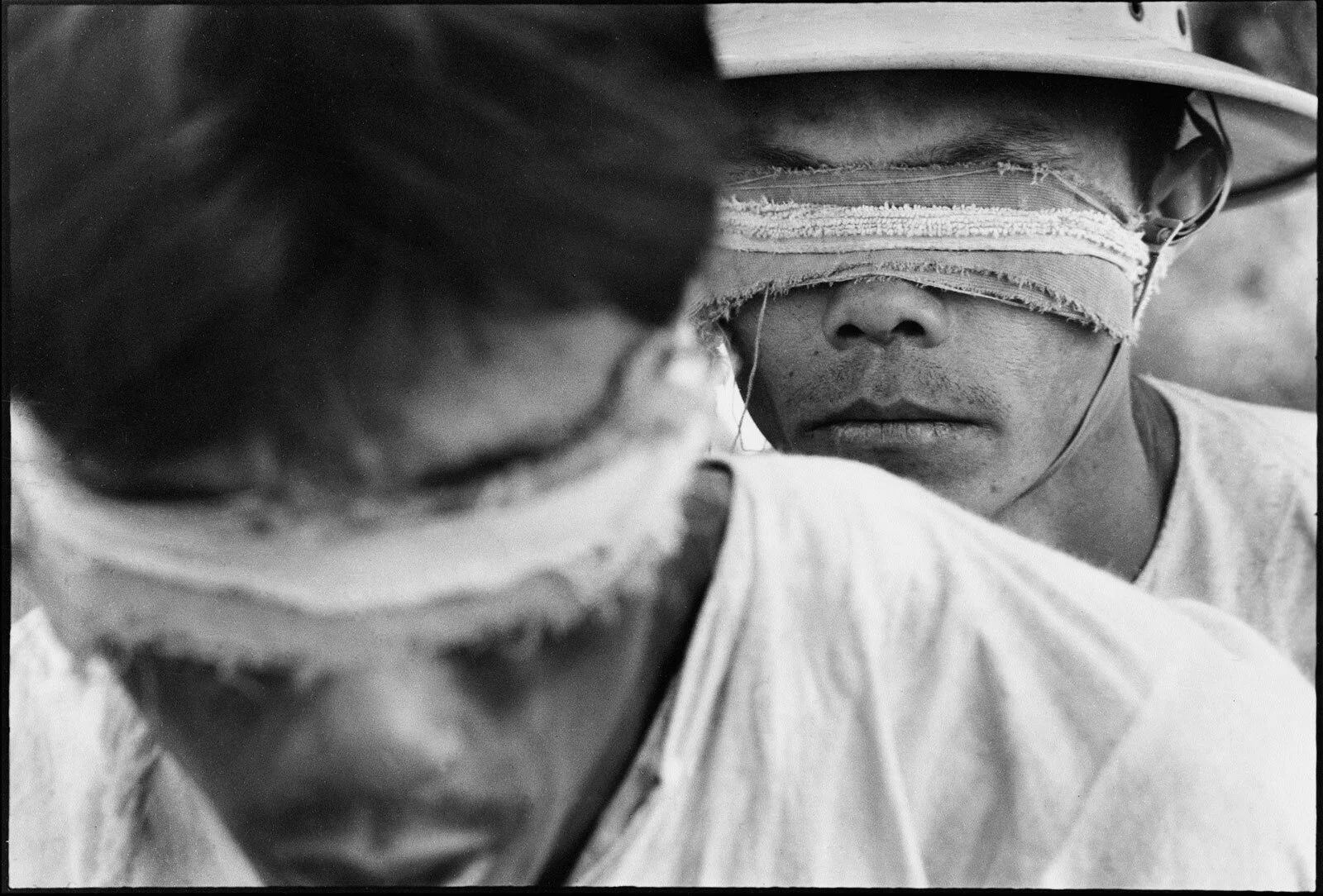

1st Cavalry men capture a Vietcong solider, Bong Son, February 1967. ©Dotation Catherine Leroy

Talk about the editing process. What was the deciding factor for what went in and what was left out? What was the direction? How did you build that story?

The first radical move for the film was that it would be driven by her photography. A lot of people talk about the power of the still image, but when they are tested by making a film, they punt and use footage. The footage of carpet bombing that Herzog uses that is extraordinary, you see it in Apocalypse Now. So the first big move was saying I’m not going to do that. She’s a photographer and the main thing I want this film to do is to tell her story through the photographs she took, through pieces of the memoir she had written and letters she sent home to her parents. Rather than telling the story of Catherine Leroy, I want to let Catherine Leroy tell the story of the war. Primarily the film needed to be Catherine’s chance to make a film, or to have the film that she might have made.

Once I understood that was going to be the heart of it, that there were going to be sequences of images and her narrating her experience — from there it was easy.

Then I did a number of interviews, but only with those who were in Vietnam with her. That was a rule, too. I didn’t want people who didn’t know her, I didn’t want people saying how great and important she was. I wanted people who were with her in Vietnam and could tell stories about what she had done. When I did use those interviews with Duncan, Page and McCullin—in fact the most famous living photographers who covered Vietnam—I wanted to hear what they had to say about Catherine and what she was like and what the context was like when she was there.

They were uncut interviews, I didn’t slice and dice them. Instead I put portions of them onscreen uncut. The final structuring of the film was the letters that she wrote, primarily to her mother. And those I had narrated over contemporary footage I made in Vietnam while retracing her path.

She wanted first and foremost to be treated as a serious journalist covering the biggest story in the world, and that was how I was going to treat her, too. I didn’t want a film that was just celebrating her ability as a woman to succeed doing her job in a man’s world. I wanted to let her do it.

Vietcong prisoners before interrogation, Mekong Delta, 1966 © Dotation Catherine Leroy

What was excluded from the film? What was not fitting in your narrative?

When I wrote the first script, it would have been a three-hour film. Things had to be cut for length. Because I was making the decision to put still images at the forefront of this film, I also had to recognize that people have a certain tolerance for that. Sequences can last for six or seven minutes, but there will be a falling-off point, where people can’t tolerate that anymore. So because the images came first, I could only have the amount of text that would fit the duration of the image sequence. So a lot was left out, and the question wasn’t so much what to take out as it was what to leave in. And what I was driven by the most was what Catherine was seeing around her. What she was observing.

There is a little about her own feelings and her relations with other people, but mostly it’s her talking about the marines when she would go out with them, what she would say about operations. Mostly she tells the story of what happened in the field.

Têt Offensive, Battle of Hué, February 1968 © Dotation Catherine Leroy

That was my main concern, even though she said plenty about herself and a lot about how she was treated as a woman. But the thing is—as McCullin says in the film—she didn’t want to be treated as a woman. And she would say as much in the letters and in her memoir, and it appears in the film. She wanted first and foremost to be treated as a serious journalist covering the biggest story in the world, and that was how I was going to treat her, too. I had to. I didn’t want a film that was just celebrating her ability as a woman to succeed doing her job in a man’s world. I wanted to let her do it.

There is that subtext in the film; she is 4’11’’, she has a lot of obstacles, there is an entrenched patriarchy, it’s a war, it’s a man’s domain. But what is the point of celebrating the overcoming of those obstacles if you don’t show the fruits of her labor? Afterwards I can tell you that it wasn’t easy, I can show you some of the difficulties she faced, that the authorities thought she was a prostitute, men would call her “girl,” want to help her dig her foxhole — but in the end Catherine, certainly with the marines in the field, she overcame all of that. She proved herself among those guys, as you can see in the photographs — they took her seriously. She got inside those battalions and those units, and they went about their business and forgot about her. Let’s see that.

There is that subtext in the film; she is 4’11’’ she has a lot of obstacles, there is an entrenched patriarchy, it’s a war, it’s a man’s domain. But what is the point of celebrating the overcoming of those obstacles if you don’t show the fruits of her labor?

© Dotation Catherine Leroy

Conflict coverage changed so much since those years. In your experience when you covered wars forty years after her what was the main difference?

Well it’s hard to generalize, but I’d say that Catherine and the journalists covering Vietnam did their jobs so well that no military force was ever going to be that accommodating to the Press again. I mean it wasn’t like that in Afghanistan when I was there, and it certainly wasn’t like that in the Middle East when I covered the Second Intifada. After Vietnam, they knew what a photographer, or a writer, could do.

Under fire near the DMZ, ‘Operation Prairie,’ 1967 © Dotation Catherine Leroy

Well it’s hard to generalize, but I’d say that Catherine and the journalists covering Vietnam did their jobs so well that no military force was ever going to be that accommodating to the Press again.

In more practical, access-related terms of covering conflict now vs. then?

You can’t compare. In Vietnam, as Jon Randal was saying in the film, you could just jump on a helicopter and go anywhere, it was like a free transportation. Like going to the subway station. Where do I want to go? I wanna go to Khe Sanh. Okay. I wanna go to Danang or to Hue, or to be with this unit, or that unit. Okay. Somehow around that time there was a certain innocence within the Macvee, the military authority, in thinking that this would not be a problem. Hell, they would even pay for it.

So she could go anywhere, she wasn’t hated by the military, she wasn’t viewed with suspicion by them, that she would expose something they didn’t want exposed. Even though, as you have seen in the film, she photographed marines beating Vietcong prisoners then smiling for the camera. Very different era. Without fear of exposure. In Afghanistan, of course, it wasn’t like that.

© Dotation Catherine Leroy

Why is it important to know her story for the photographers of today?

The first reason: if you want to learn about the Vietnam War, or about war period — look at this work. That’s the first reason, and you’ve got to honor her and take her seriously first by looking at her work.

Secondly, 21 years old , 4’11’’, with no money and hardly any equipment, but fearless, passionate — that’s what gets the job done. I think that’s the message. It’s a message of empowerment. She did not let anyone stop her. She got it done. This is an against-all-odds kind of narrative. She was able to overcome everything people threw at her. She paid the price for the rest of her life. She was haunted by what she saw and did, and she was plagued by not getting the recognition that she thought she deserved — but she did it.

It’s a message of empowerment. She did not let anyone stop her. She got it done. This is an against-all-odds kind of narrative. She was able to overcome everything people threw at her. (…) She was haunted by what she saw and did, and she was plagued by not getting the recognition that she thought she deserved but she did it.

Vietnam, 1966-1968. © Dotation Catherine Leroy

DIRECTOR’s BIO

Jacques Menasche is an award-winning writer, editor, and filmmaker. Born in Baltimore, Maryland, he began his career as a clerk at The New York Times, and has since produced reportage, books, and documentaries from around the world, covering the attacks on 9/11, the war in Afghanistan, the modernization of China, and the Palestinian/Israeli conflict, among other important stories. His writing has appeared in the New York Daily News, ESPN The Magazine, Vanity Fair, Fader, and Columbia Journalism Review in the US, The Independent in the UK, Polka in France, and Italy’s Corriere dela Sera. In 2007, “Brothers of Kabul,” his television documentary about heroin addiction in Afghanistan, produced with photographer Stephen Dupont, received Australia’s Walkley Award for Best Television News Feature. In 2011, his documentary about a first-grade class near Ground Zero, “The Class of 9/11,” led off PBS NewsHour’s 10th anniversary coverage. In 2016 he completed “Cathy at War,” a documentary feature about Catherine Leroy, the greatest female photographer of the Vietnam War. A graduate of the Columbia University School of Journalism, he teaches at the International Center of Photography in New York.

The film “Cathy at War” is produced by the Dotation Catherine Leroy

Edited by Alain Rimbert

Voiced by Tal Halevi

All Images © Dotation Catherine Leroy 2021

dotationcatherineleroy.org

Interview by Alexey Yurenev

© Dotation Catherine Leroy