Memory is in the Hands of Women

An Interview, in English and Spanish, with Zahara Gómez Lucini

by Daniela López Amézquita

Receteario para la memoria is a photographic, culinary, and social project created by artist Zahara Gómez Lucini, in collaboration with Las Rastreadoras del Fuerte, a group of women based in Sinaloa that is dedicated to finding the bodies of victims of forced disappearance*. With designer Clarisa Moura and cultural producer Tai La Bella Damsky, they have created a photographic and culinary book dedicated to the recipes that Las Rastreadoras once cooked for their loved ones, now missing.

*a secret abduction or imprisonment by a state or political organization, or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organization

How did you start working with the theme of forced disappearance?

I am Spanish-Argentinian and I have siblings who were born in Argentina. The youngest of us, which includes myself, were born in Spain. My father left Argentina in ‘78. He was a journalist and he fled in exile. So, I feel that the figure of the missing person is something that I have grown up with since I was very young, because my father spoke about it often. It's very difficult for an adult, but for a child, the idea of forced disappearances is something very strange. So, the subject is fundamental in my life.

I have memories of going to Argentina with my dad when I was older. He introduced me to the mothers of Plaza de Mayo because he was with some of their sons. It was something familiar but strange at the same time. In the College of Art History, I specialized in the history of photography and my thesis was on the representation of victims of forced disappearance in Argentina.

EAAF working tools, Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team, 2017

What was your initial approach to the project? What was your first idea?

I was in Argentina with the forensic team there, in Chile with the women of Atacama – who had been looking for their missing loved ones over a 30-year period. I also followed the Colombian forensic team, the Guatemalan forensic team, and the Mexican forensic team. When the first marches for the 43** took place, I remember one video in particular where the civil police forcibly removed a guy in the street. The guy started screaming his name and it reminded me very much of the stories that my aunt and father had told me. Of course the circumstances are different, but it continues to be the same methodology of terror. The video had a huge impression on me. At the same time that I was getting to know the forensic teams, I got to know the Rastreadoras del Fuerte. What I realized is that the Mexican forensic team is made up of very few people, they are quite alone, they don't have that structure that the others have, nor do they have the same history. In addition, they depend on the attorney general’s office and they have limited autonomy.

** the 43 students of the Escuela Normal Rural de Ayotzinapa [a teacher’s training college] that fell victim to forced disappearance in Iguala, Guerrero, Mexico in 2014

“There was a restlessness about the way we could draw attention to and invite people to take a stand on such a delicate matter, but it cannot be a fight for only civilian organizations or human rights defenders. This has to reach other groups.”

Tracking Wednesday for Las Rastreadoras del Fuerte. Los Mochis, Sinaloa, 2017

I went to Los Mochis, Sinaloa to see the mothers of the victims of forced disappearance and we got along well. It was very emotional. I started to work with them, at first with a more documentary approach. We worked a lot and there was an exhibition at the Centro de la Imagen of a collaborative project where I presented all of my forensic work. It was a turning point because the exhibition was very beautiful but only photographers and four human rights defenders attended. So then, why are we doing this?

I started to document [the facts] for them, but I was no longer working for myself. I didn’t see the point. At the same time, I saw that when you are with these groups, journalists would come, very good journalists, but they would end up leaving with their story and never return. I also realized that [the women] were telling the same story, in the same way, every time because in reality they were always asked the same questions. The problem lies with us.

That was when I said to myself, ok, this doesn’t work, I’m not interested. It's great that someone comes to tell your story, then takes it elsewhere, publishes it, talks about it, it's incredible, but in reality nothing is left here, right? I was not interested in having a portrait of a mother or her holding a portrait of her missing son.

“It all began with that strong feeling of restlessness to do the project with them and for their signatures to be real, not just an act of charity.”

Hole made by a blade and traces of clothing found on a tracking day. Los Mochis, Sinaloa, 2018

That is the image I have of the mothers of Plaza de Mayo.

Argentina, in that respect, has a very interesting body of work about memory. Much is produced regarding this topic and it is very interesting because I think that the artistic community, not just the photographic one, has searched for many forms [of expression]. I feel that there have been various narratives: the narratives of the 80’s, the narratives of the children of missing persons and also, there is another narrative forming.

For me, this last one is the one in which I see myself and that has a bit more distance from those other stories so that it can create a tangible reflection or a new approach that goes in other directions. Not because the others are not valid, they have allowed us to begin to also question things from a visual perspective, from an artistic perspective, and not from a historical perspective.

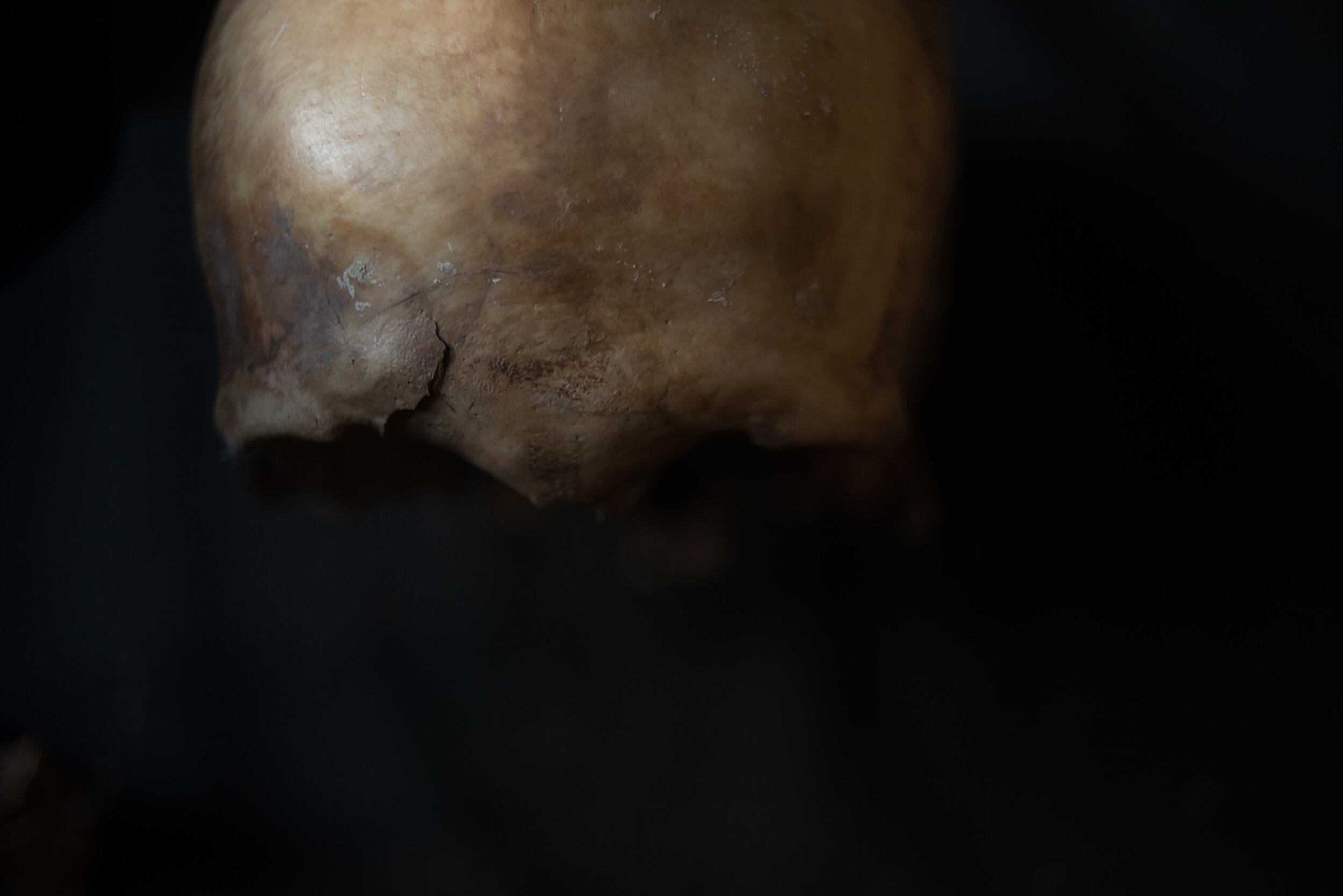

Seeing the Triptychs and Diptychs that you did with the photographs of bones and maps, gives me the idea of finding in the image the paths where these remains were found. How did you begin the concept of creating these images with the found bones?

It occurred to me after working with the Argentinian forensic team. In Argentina and in Guatemala I did a series of photographs of the bones and tools that were used. It’s a huge collection. I then started to make more matches. For example: I would show a bone that was found in Tucumán and I looked on the map to see what Tucumán looked like. That is when I started to construct landscapes, also keeping in mind the fact that, literally, you walk over the dead, beyond forced disappearance, in life you walk over memories, over layers.

Afterward, I started the paper landscapes, this idea was born through thinking that documentary writing was not enough for me. I started to do these prints of places where I had been told that mass graves had been found in Mexico, so using the coordinates I started to print them and once they were printed I started to give it form and I took the photos that, for me, are like paper sculptures. Also present was the idea of working with your hands, of materializing something.

“Suddenly, I realized that the act of cooking in itself could be an amazing tool because many of these women had never cooked these dishes again. So they begin to talk about the missing person but from a different place”

Left: Sonia Chanes cooks “Capirotada” in her home, the favorite dish from her son Pablo Dean who disappeared on May 10, 2018. Sonia looked for him and found on December 4, 2019

Right: The chiltepin chilli from Manky. María Cleofas Lugo looks for her son Juan Francisco who was disappeared on June 19, 2015. Manky is still looking for him.

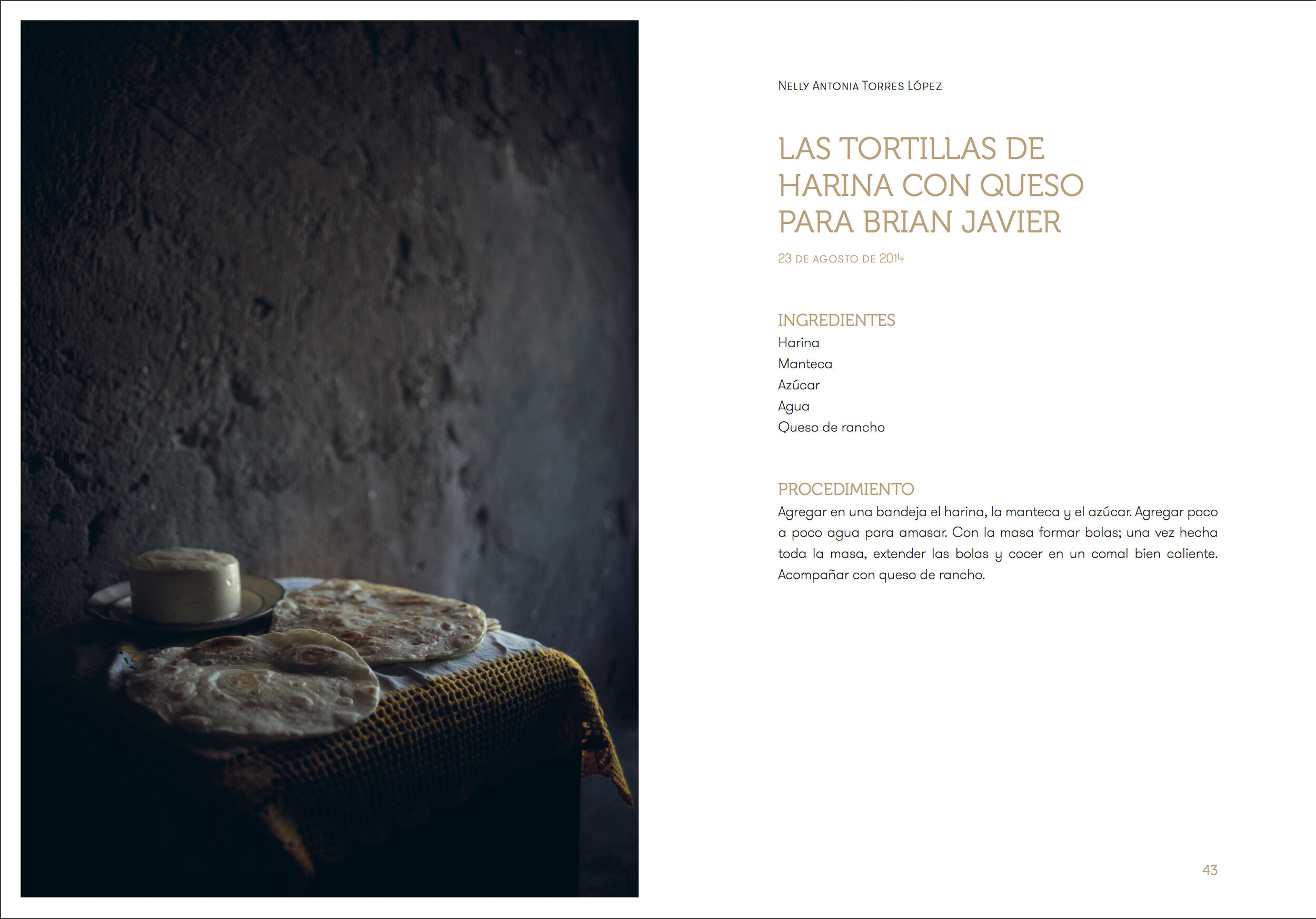

In what stage of the project did you decide to go beyond documentary photography and show the more intimate side of Las Rastreadoras through food and their cuisine?

My journey with them has been an opportunity for something co-authored. I was very worried about what the authorship of these women could be. I wanted to ask them “where is your signature?” They ended up being photos of food but I never planned it that way. There was a restlessness about the way we could draw attention to and invite people to take a stand on such a delicate matter, but it cannot be a fight for only civilian organizations or human rights defenders. This has to reach other groups.

I agree and from my point of view I believe that in México–if you are not physically present with the activists, if you are not part of a University or student organization, if you are not there supporting the protest because you are working or have other activities–you feel as if you were looking at something from a distance, but you do not know how to help. Even if you are conscious of the fact that you should fight for the cause. That is why I think that through the kitchen you not only achieve empathy but really take the memory into other homes.

That is, in part, the overall goal but it was not so clear to me at all. It all began with that strong feeling of restlessness to do the project with them and for their signatures to be real, not just an act of charity. It was more about asking them: Where are you? What is it that you are signing in the book? So, when Manky prepares a flan and she does it her own way, I found a solution to that problem as well.

We started working on this project in 2018. In the end, the act of taking photos was brief, the evocative power of cooking, the whole process of preparing the dish, getting together and eating, all of that was what accompanied the photos, I had never thought about that.

“This book invites you, while preparing pizzadillas for Roberto, to think of him, even though you may not know him, to bring him to life, to invite him to your table.”

Skull of a man found in the Tucumán region by EAAF. Argentina, 2017

Suddenly, I realized that the act of cooking in itself could be an amazing tool because many of these women had never cooked these dishes again. So they begin to talk about the missing person but from a different place: “oh no, he loved this” or “he was always bothering me while I was trying to cut meat.” For me that embodies the person that we are talking about.

Without planning it, you are nourishing yourself with memory. You are eating a meal prepared with love but it was not meant for you. This book invites you, while preparing pizzadillas for Roberto, to think of him, even though you may not know him, to bring him to life, to invite him to your table. I truly think that food has that tremendous power.

Do you believe that the act of waiting, that we usually associate with women, is what moves someone to the act of searching? Do you think it is a gender issue?

If you talk to Mirna, she says that when someone you love disappears, your life as you knew it is gone, and will never be the same. I think when you are a mother – I am not a mother but I can imagine – you cannot ignore this and you drive yourself crazy. The same thing was said about the “crazy” women from Plaza de Mayo, in Los Mochis, they call them “the crazy shovel ladies.”

In a conversation with the Colombian Forensic team (forensic teams are generally formed by women), I was shocked and asked them “What is going on? Why are there so many women here?” One of the ladies replied, “It’s simple, men destroy and we build up.” This is a really nice answer, and it got me thinking that memory is in the hands of women. In the academic world, there are many women that have written about memory, it’s construction, it’s importance. Forensic work dedicated to mass graves is about making memory, not forgetting. It’s about recognizing.

I have not come to a conclusion about this. Obviously there are a lot of factors mixed together, among them a social issue because, in reality, many women are homemakers, perhaps they have more time. But, at the same time, a lot of families are torn apart after a disappearance. There is a lot of separation between husbands and their wives. The women are left alone and they continue to search. A part of me thinks that women, due to their story as a gender, and because of the issue of the menstrual cycle, she has a different temporal consciousness that is almost instinctual. There is an animal-like capacity when finding strength where there is none left.

“In the academic world, there are many women that have written about memory, it’s construction, it’s importance. Forensic work dedicated to mass graves is about making memory, not forgetting. It’s about recognizing.”

I like the idea of photography as a tool because it tells me about a way of working collaboratively. Do you think that should be the main objective of documentary photography nowadays?

I was already tired of the photo being thought of as “Oh! The great photo and the great photobook!” because in reality you realize that we are five people looking at ourselves and applauding one another’s projects. To think about photography as a tool and nothing more frees you so much because, in reality, if tomorrow the tool needs to change for the sake of the project, you change it and there’s no harm done. I would say that in this project, photography is not even a tool, it is a document, the tool is the cooking in this case.

I think that above all, when it comes to social issues, I do not like to think about doing incredible work and not think about the community. What do they need? What do they want to say? Because you come from a position of privilege, and you have to accept that and not fight it. I had the privilege of studying what I wanted to, the privilege of being able to dedicate myself to what I have chosen to do, a series of things that I believe comes with responsibility.

Yes, and I think that it is very important to recognize our privilege to understand how to approach the topic.

Of course! And you have to make peace with that. Making peace doesn’t mean you will never be conflicted, but you have to know where you stand and do that exercise every so often. For example, this time of the pandemic has been interesting in that regard, because you have a house, you have doors, you have running water. Many of the Rastreadoras contracted COVID and I thought about them and how difficult it is for them. It’s not just that you get sick, we are talking about houses that don’t have doors, so you have to be on lockdown for 14 days which means the whole family is infected. What’s important is to be conscious of where you stand so that you are able to propose things, perhaps, from a place that is fair and just.

Diptych from a landscape between a bone trace and an aerial view where the bone was founded. Argentina, 2017

Personally, and as a Mexican, I have a strong connection to food. When I speak with Mexicans that are also living in New York, one of the first questions we ask ourselves is “What is the first thing you are going to eat when you go back to Mexico? Do you think that through cooking, there could be a deeper consciousness of the problem of forced disappearance?

In the 60’s, forced disappearances were widespread in Latin America, but from the State as a dictatorial force. In Mexico’s case it’s interesting because forced disappearance en masse happens in a democracy, in a “Rule of Law.” Obviously, I am using quotations when I say this because the methodology remains the same. Many people that are a part of the large groups of armed narcos were in the military. There is a training that comes from the same place even though it is being applied in another area. Likewise, in Argentina, when forced disappearances were perpetrated there is this huge discourse of “they must have done something.” The stigmatization is one of the things that has to be stopped.

We must fight against forced disappearance even though it is not necessarily in our hands, Fighting against stigmatization of the missing and their searching families, however, is.

Also, on a positive note, when I met all these groups of women, whether they be in forensics or search groups, there was a powerful network of resistance and we shouldn’t forget that. They are not just victims, they are a network. Mirna knows the Argentinian forensic team and others and we must shed light on that because it is very interesting work.

Speaking with the women of Atacama, they didn’t have any idea about disappearances in Mexico, and the women in Mexico did not have any idea that in the south there were women searching. I think that our position is to be able to facilitate this bonding because it means that they are not alone and that gives them a lot of strength.

“when I met all these groups of women, whether they be in forensics or search groups, there was a powerful network of resistance and we shouldn’t forget that. They are not just victims, they are a network.”

Tracking. Los Mochis, Sinaloa, 2019

Purchase the book here

Artist BIO

Zahara Gómez Lucini (b. 1983) is an Argentinian-Spanish photographer who was raised in France. She has an MFA in Art History from the Paris-Sorbonne University. Her work explores political and social stories of violence. She utilizes archival material, collaborates with human rights organizations and does field work in the areas where the disappeared are being searched in order to examine the incomprehensible through the construction of collective memory.

She has worked as Production and Exhibition Coordinator at Magnum Paris. Her work has been showcased in many exhibitions such as “Images Singulières”, in Sète, France (2019), “Tesoros” in CCK, Buenos Aires (2018), “Natura” in CASA Gallery, New York (2018), and “La Playa” in the XVII Photography Bienal in Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City, (2017). Her artistic practice has been recognized by the Photography Grant AHRC (2017). She teaches in Mexico City at the Escuela Activa de Fotografía, Centro ADM, Gimnasio del Arte, and Centro de la Imagen. She is part of Women Photograph and Co-founder of Fotógrafas en México. Her most recent collective project Is this tomorrow was a finalist in the Arles Photobook Awards 2019.

sobre el artista

Zahara Gómez Lucini (n. 1983) es una fotógrafa argentino-española, criada en Francia. Estudió una Maestría en Historia del Arte en la Sorbona de París. Su trabajo explora historias político sociales sobre la violencia en los territorios. Usa la investigación de archivo, la colaboración con organizaciones de derechos humanos y el trabajo de campo en zonas de búsqueda de desaparecidos, para investigar aquello que resulta incomprensible y que se reivindica a través de la construcción de la memoria colectiva.

En el ámbito profesional ha trabajado en Magnum Paris como Coordinadora de producción y exhibiciones. Su trabajo ha sido expuesto en diferentes lugares: “Images Singulières” en Sète (2019), “Tesoros” en CCK, Buenos Aires (2018), “Natura” en CASA gallery, NY (2018), y “La Playa” en la XVII Bienal de fotografía en el Centro de la Imagen, CDMX (2017). Su práctica artística ha sido reconocida por la beca de fotografia AHRC (2017). Imparte clases en diferentes centros en Ciudad de México: Escuela Activa, Centro ADM, Gimnasio del Arte y Centro de la Imagen. Es parte de Women photograph y cofundadora de Fotógrafas en México. Su último proyecto colectivo, Is this tomorrow, fue finalista en los premios de fotolibros de Arles en el 2019.

entrevista

Recetario para la memoria. La memoria está en manos de las mujeres.

Entrevista a Zahara Gómez Lucini por Daniela López Amézquita

Recetario para la Memoria es un proyecto gastronómico, fotográfico y social creado por la fotógrafa Zahara Gómez Lucini, en colaboración con as Rastreadoras del Fuerte, un grupo de mujeres fundado en Sinaloa que se dedica a buscar cuerpos de víctimas de desaparición forzada y que junto con ellas, la diseñadora Clarisa Moura y la productora cultural Tai La Bella Damsky, han creado el libro fotográfico y culinario dedicado a las recetas que Las Rastreadoras le hacían a sus desaparecidos, nuestros desaparecidos.

¿Cómo empezaste a trabajar con el tema de la desaparición forzada?

Yo me he dado cuenta, no era muy consciente hasta hace poco, pero soy de familia Argentina. Soy española-argentina pero tengo hermanos que nacieron en Argentina y, digamos que la última camada, los más jóvenes de los que yo soy parte, nacimos en España. Mi papá salió de Argentina en el 78. Él era periodista y salió en exilio. Entonces siento que la figura del desaparecido es algo que yo he mamado desde muy pequeña porque en mi casa se hablaba mucho, mi papá hablaba mucho de eso. Obviamente con ojos de niña no sabes ni qué carajos es y se convierte en algo un poco mitológico. Es muy difícil para un adulto pero para un niño lo del desaparecido es una cosa extrañísima ¿qué es?.

Entonces el tema es fundamental en mi vida. Cuando empecé a estudiar de grande, no sé, te cuento porque esto es una charla amable, tengo recuerdos de ir a Argentina con mi viejo. Mi viejo me presentaba a las mamás de Plaza de Mayo porque él estuvo con hijos de algunas de ellas. Digamos que era algo familiar pero extraño a la vez. Después empecé a estudiar en la facultad de Historia del Arte, me especialicé en la historia de la fotografía y mi tesina fue sobre la representación de los desaparecidos en Argentina. Venía muy clavada con eso y sigo desde hace mucho tiempo. Aunque después fotográficamente no lo manejaba desde la consciencia.

¿Cómo fue tu primer acercamiento al proyecto? ¿Cuál fue la primera idea?

Después de eso empecé a acercarme a los equipos forenses. Estuve en Argentina con el equipo argentino forense, en Chile con las mujeres de Atacama –que estuvieron buscando durante 30 años ahí a sus desaparecidos–. Me acerqué también al equipo forense colombiano, al equipo forense de Guatemala, al equipo forense mexicano. En México a mi me pasó algo. Cuando fueron las primeras marchas de los 43*, recuerdo un video en particular donde policías de civil se llevaron a un chavo en la calle. Como se grabó entonces el tipo empezó a gritar su nombre y me recordó mucho a las historias que me han contado mi tía y mi papá. De verdad fue como un ¡órale!, quiero decir, no es lo mismo obviamente los medios cambian, obviamente las circunstancias parecen ser diferentes, aunque yo no estoy tan convencida de eso porque sigue siendo la misma metodología de terror. Me marcó mucho el video y me acuerdo que hablé con mi tía. Mi tía vive en Argentina –ella también fue montonera en su momento– y estuve mucho tiempo hablando con ella porque ella me había contado esas historias de cuando se llevaban a chavos en Argentina, ellos gritaban su nombre. Obviamente no había grabación pero había redes y bueno a este chico que era estudiante de la UNAM lo sacaron el mismo día porque la familia fue a la fiscalía y se armó todo un revolte ¿no? Eso también fue un tema muy fuerte para mi.

A la par que empecé a conocer a los equipos forenses comencé a conocer a las Rastreadoras del Fuerte. Lo que me di cuenta es que el equipo forense mexicano está en bragas, qué decir, realmente son muy poquitos, están muy solos, no tienen esa estructura que tienen otros que tampoco tienen esa historia. Además, dependen de la procuraduría y tienen una autonomía muy relativa. Entonces, me fui a Los Mochis, Sinaloa y pasó algo que nos entendimos muy bien. Yo no sé si fue el carácter del norte con el que yo me siento agusto. Había conocido otros grupos de familiares, quiero decir, con ellos había muy buena onda pero no hubo un match ¿no? Con las mujeres del norte sí se hizo un match muy emocional. La primera noche empedamos cuando nos conocimos, era una cosa muy familiar y entonces comencé a trabajar con ellas. Al inicio desde la fotografía documental clásica: hice registro y fui al rastreo. Pero empecé a ir muy seguido, muchas veces al año. Entre tanto hubo una exposición en el Centro de la Imagen de un trabajo colaborativo donde yo ya presentaba toda la parte de mi trabajo forense. Esa exposición fue también un parteaguas porque fue mucho trabajo y en realidad, la expo fue muy bonita y demás, pero solamente fueron fotógrafos y cuatro defensores de derechos humanos. Entonces ¿para qué estamos haciendo esto? Dejé de hacer foto con ellas pero seguí yendo y empecé a hacer registro muy puntual para ellas, como de “oye, necesitamos no sé qué” o “échanos la mano para una proyección” pero ya no estaba trabajando para mi. Ya no le veía el sentido y a la vez se mezclaba que cuando estás con estos grupos, claro que se acercan periodistas, y muy buenos periodistas, gente brillante, no quiero sonar mal con eso pero al final se van con la historia y nunca más vuelven. Y pasando mucho tiempo con ellas también me di cuenta de que estaban contando la misma historia de la misma manera siempre, porque en realidad les estaban haciendo las mismas preguntas. Entonces igual el problema es nuestro y no de ellas. Si siempre haces la misma pregunta, siempre van a contestar igual, termina siendo un guión y lloran en el mismo momento y se convierte en algo medio extraño.

De repente todo eso me conflictuó mucho porque pues se van tejiendo relaciones más personales. Fue ahí cuando me dije ok entonces esto no funciona, a mi no me interesa. Que bien que alguien venga a contar una historia, se la lleve fuera, se imprima, se hable, está increíble pero realmente no queda nada aquí ¿no? Y yo personalmente estoy muy cansada de la narrativa de la mamá llorando, de la mamá con el retrato del hijo del desaparecido.

Porque además esa es la imagen que tenemos de las madres de Plaza de Mayo.

Sí, totalmente y digo, Argentina en ese sentido tiene un trabajo de memoria muy interesante. Se sigue produciendo mucho al respecto y es muy interesante porque creo que el cuerpo artístico, no sólo fotográfico, sí le ha buscado muchas formas. Yo siento que ha habido varias narrativas: las narrativas de los 80, las narrativas de los hijos de desaparecidos y, aparte, viene otra narrativa. Para mi esta última es en la que más me reconozco o la que más me interesa indagar y que ciertamente tiene un pelín de distancia con esa historia que creo que te permite tener una reflexión plástica o una apuesta plástica que va por otros caminos. No porque los otros no sean válidos, realmente los otros son los que han permitido que se pueda empezar a cuestionar también desde lo visual, desde lo plástico y no desde la historia o la importancia de contar una historia.

Al ver los trípticos y dípticos que hiciste con las fotografías de huesos y los mapas, me da la idea de encontrar en la imagen los caminos donde se encuentran estos restos. ¿Cómo empezaste la idea de crear estas imágenes con los huesos encontrados?

Pues mira, eso se me ocurrió después de trabajar con el equipo forense Argentino. Estando en Argentina y en Guatemala hice una serie de fotografías sobre las herramientas de trabajo y de huesos pensando qué hacer con eso. Es una colección tremenda, y de repente empecé a registrar, por ejemplo: este hueso se encontró en Tucumán y empecé a buscar en el mapa cómo se veía Tucumán. De repente dije hay que empezar a armar paisajes también pensando en esta cuestión de que tal cual caminas sobre muertos, más allá de la desaparición forzada, en la vida pues vas caminando sobre memorias, sobre muertos, sobre capas. Entonces esos paisajes re-creados o construidos sí fue un ejercicio de decir: vamos a buscar en esa parte el hueso que pertenece a esta zona ¿Cómo se puede comunicar esto? Entonces empecé por las herramientas y después aparecieron estos paisajes construidos. Después comencé con los paisajes de papel, esta idea nació de pensar que la escritura documental no me bastaba, que aunque para mi sí es importante seguir en ella ya no la creo como autónoma. Empecé a hacer estas impresiones de lugares donde me habían dicho que habían encontrado fosas en México, entonces trabajando con las coordenadas empecé a imprimir eso y una vez que estaba impreso comencé a darle forma e hice las fotos que para mí son como esculturas de papel. También estaba presente la idea de trabajar con las manos, de materializar algo. Y después de mucho trabajo de campo con estas doñas, en especial con las Rastreadoras –desde la cosa más documental hasta entender estos paisajes que están en medio de la nada– cuando estás ahí con ellas en medio de la nada sin cobertura, sin red, es cuando me puse en contacto con Artículo 19 para coordinar temas de seguridad. Lo que quería es, según las normativas de seguridad, estar con ellas. Lo que hacíamos era meterse a la boca del lobo, entonces que loco que ellas lo hagan mínimo dos días a la semana y que realmente es una sensación de estar en en medio de… no sé, de ser una aguja en un pajar. Nos pasa algo y olvídate, quiero decir, nadie sabe dónde estás y es el desierto, es imposible. Aunque ellas son de allá y se han ido formando para trabajar en esto, claro que se convierten en especialistas del territorio. Pero, al final del día, no es su oficio. Entonces se crean situaciones muy extrañas porque a pesar de eso ellas van, asumiendo el riesgo de que se pueden perder.

Más allá de eso, te vas dando cuenta de que se han ido especializando en otros temas, por ejemplo, en reconocer un hueso de otro, yo no sé reconocer un hueso de otro pero ellas ya saben reconocer el hueso de una falange. Llegan a tener un nivel de expertise tremendo pero hay que entender que cuando empezaron se emocionaban porque encontraban un hueso de caballo. También fue lo que pasó con las madres de Plaza de Mayo, se convirtieron en super especialistas en derecho y bueno, en general, esto pasa con todas estas mujeres, siempre son una referencia porque han aprendido a hostias.

¿En qué estado del proyecto decidiste ir más allá de la fotografía documental y mostrar el lado más íntimo de Las Rastreadoras a través de la comida y sus cocinas?

Lo que he sentido en mi camino con ellas es que ha sido una apuesta por algo en co-autoría. Me preocupaba mucho cuál podría ser la autoría de estas mujeres porque

yo no quería una foto de una mamá llorando pero tampoco quería decirles “oye, mira por la ventana porque aquí hay una luz bonita”. Yo más bien quería decirles ¿dónde está tu firma? Y bueno, terminaron siendo fotos de cocina pero nunca me lo había planteado desde ahí. Y sí estaba esa cuestión de mucha inquietud para mí de cómo llamamos la atención e invitamos a tomar postura sobre un tema tan delicado pero que no puede ser sólo una lucha de los grupos civiles de búsqueda ni de los defensores de derechos humanos. Esto tiene que traspasar estos círculos.

Sí y desde mi punto de vista creo que en México, si no estás con los activistas presencialmente, si no eres parte de alguna universidad o cuerpo estudiantil, si no estás presencialmente apoyando en marchas por trabajo u otras actividades, estás en medio viendo que algo está pasando pero no sabes cómo ayudar aunque estés consciente de que se debe luchar por ello y creo que a través de la cocina no sólo puedes lograr esa empatía sino que realmente llevar esta memoria a los hogares.

Claro, esa es un poco la apuesta pero yo no lo tenía tan claro, para nada. Todo inició con esa inquietud muy fuerte de obviamente quiero firmar el proyecto pero quiero firmarlo con ellas y que la firma de ellas sea real, que no sea una cosa de benevolencia sino de ¿dónde estás tú? ¿qué estás firmando tú en el libro? Entonces cuando Manqui hace un flan y lo hace a su manera, entonces para mí se soluciona eso también. Yo no puedo opinar sobre eso, ni yo ni nadie, quiero decir, tú haces el platillo. Empezamos a trabajar en este proyecto en el 2018, pero yo no le entré desde ese punto de vista. Pero el poder de evocación de la cocina, estar en las cocinas, porque al final el acto fotográfico fue muy corto pero igualmente, todo el proceso de cocina, de juntarse, de comer, que fue lo que acompañó la fotografía, nunca lo había pensado. De repente me di cuenta de que sí podía ser una herramienta y una increíble porque había mujeres, muchas de ellas, que no habían vuelto a cocinar ese platillo. Entonces de repente empiezan a hablar de esa otra persona desde otro lugar de “ay no, es que a él le encantaba esto, esto no le gustaba, o me molestaba cuando yo estaba cortando la carne”. A mi eso me da corporalidad de quién estamos hablando, de ¡ah! no le gustaba esto o no se aguantaba entonces el platillo nunca terminaba hecho porque era un ansioso y se lo comía. Sin tenerlo planteado ha sido un honor poder compartir con ellas porque te estás alimentando de memoria, tal cual. Te estás alimentando de una comida hecha con amor y lo que quieras pero que no es para ti. Y yo ahí de repente le di otra capa a todo esto, que no tenía planteado desde un inicio, que es hay que hacer comidas, hay que hacer eventos para hablar de desaparición pero a través de esto. Cocina las pizzadillas para Roberto pensando en Roberto, aunque no lo conozcas, no importa pero hazlo presente, invitalo a tu mesa, que eso a lo mejor ya tiene un nivel performático. Sí, creo que la cocina tiene ese poder tremendo.

¿Crees que la idea de la espera, que es algo que se relaciona mucho con las mujeres, sea lo que conlleve a la acción de buscar? ¿Crees que sea una cuestión de género?

Claro, pero yo creo que la reflexión no viene desde ahí. Si hablas con Mirna y demás, ella dice que cuando te desaparecen a alguien, tu vida tal y como la conoces ya fue y nunca va a volver. Creo que cuando eres madre –yo no soy madre pero me imagino– no puedes pasar de alto eso y entonces te vuelves una cabezota loca. Lo mismo que decían de las locas de la Plaza de Mayo en los Mochis, dicen las locas de las palas. Recuerdo que en una conversación que tuve con el equipo forense colombiano (los equipos de búsqueda forenses son, por lo general mayoritariamente de mujeres) a mi me chocó y les pregunté “¿qué onda? ¿por qué hay tanta mujer metida acá? no entiendo”. Entonces una de las chicas me decía “no pues fácil, los hombres destruyen y nosotras construímos”. Esa es una respuesta muy linda y, a la vez, a mí sí me ha hecho pensar mucho que la memoria está en manos de las mujeres. Cuando lo ves en el mundo académico hay muchísimas mujeres que han escrito sobre la memoria y sobre la construcción de la memoria y la importancia de la memoria. El trabajo forense dedicado a las fosas comunes es hacer memoria, es no olvidar, es reconocer. Yo no he llegado a una conclusión con eso, obviamente se mezclan muchas cosas, entre ellas una cuestión social porque efectivamente muchas mujeres están en la casa, digamos que tienen más tiempo. Pero a la vez muchas familias se des-construyen después de una desaparición, hay mucha separación del esposo y de la mujer, lo que sea, se desentienden y se van y las mujeres se quedan solas y siguen buscando. Hay una parte de mi que piensa que la mujer, por su historia como género y a la vez por su particularidad de esta cuestión de lo cíclico, de la menstruación, del ciclo, tiene una conciencia temporal diferente que viene de fábrica. No sé si sea así pero sí lo he pensado, no sé si eso haga una relación diferente al tiempo. Hay hombres que también se dedican a buscar pero son los menos. Hay también una cuestión de maternidad que –aunque yo no soy mamá, mi hermana me ha contado– existe una situación bestial también de sacar fuerzas de donde no las hay.

Me gusta esta idea de la fotografía como herramienta porque me habla de una forma de trabajar colaborativamente. ¿Crees que actualmente ese debe ser el papel de la fotografía documental?

Sí, pero más bien la fotografía como un fin. Yo ya había estado cansada de la foto como ¡oh! la gran foto y el gran fotolibro porque en realidad te das cuenta que somos cinco personas mirándonos y aplaudiendo los proyectos los unos a los otros. Creo que quedarse ahí es un error. Pensar que la fotografía es una herramienta y solo eso libera mucho porque en realidad si el día de mañana la herramienta tiene que cambiar para el bien del proyecto pues se cambia y no pasa nada. Tal vez vas a hacer otra cosa, porque le va a dar más sentido, le va a dar más fuerza. Yo te diría que en este proyecto la fotografía no es siquiera la herramienta, es el registro, la herramienta es la cocina en todo caso.

Cuando empecé con este proyecto lo hablé con compañeros de oficio y de repente me decían no pues vas y les pagas para hacer las fotos. No, yo le digo a Mirna que le doy dinero para hacer unas fotos y me da una patada en la boca y aparte yo no me quiero vincular así en ese proyecto. Apenas me enteré de esta nueva forma de trabajar, que de repente fotógrafos y fotógrafas le están pagando a un fixer para ir a hacer las fotos. Son increíbles las fotos pero no han hecho un trabajo de investigación, no han hecho un trabajo de acercamiento. Entonces ¿cómo es ese vínculo? El fixer nunca es reconocido, ni el ayudante ni quien sea ¿Qué has hecho? Has ido con tu cámara y has hecho una foto ¿y? Yo no quiero hacer foto desde ahí, no me interesa. Y sí creo que sobre todo en cuestión de temas sociales, no me gusta pensar en hacer un trabajo increíble y no pensar en la comunidad: ¿qué necesitan ellos? ¿qué quieren contar ellos? porque sí, sea lo que sea, aunque sea que la pases muy mal, tú vienes con mucho privilegio y eso también hay que aceptarlo y no pelearse con eso. Yo tuve el privilegio de haber estudiado lo que he querido, el privilegio de poder dedicarme a lo que he decidido, bueno, una serie de cosas que creo que sí te hace responsable.

Sí y creo que es muy importante reconocer nuestros privilegios para saber cómo acercarnos al tema.

¡Claro! y hay que hacer las paces con eso. Hacer las paces no quiere decir que no tengas conflicto nunca pero hay que saber dónde está uno parado y hacer ese ejercicio de vez en cuando. Por ejemplo, el momento pandemia ha sido interesante para eso porque es decir che, tienes una casa, tienes puertas, tienes agua corriente. Muchas de las Rastreadoras se enfermaron del Covid y yo pensaba en ellas y en que es muy difícil. No es sólo que te enfermes, estamos hablando de que son casas que no tienen puertas, entonces te tienes que encerrar 14 días y eso quiere decir que ya toda la familia está contagiada. Lo importante es tener consciencia de saber dónde estás parada para poder proponer las cosas tal vez desde un lugar más justo.

¿Crees que este tipo de trabajo en colaboración cambie el destino de la fotografía documental?

¡Uy! Yo creo que ya lo está haciendo. El trabajo de Anita Puchard Serra creo que va por ahí, ella no sólo es fotoreportera sino que también es arquitecta entonces dibuja y eso mete a sus proyectos. Como te decía hace un rato, no es sólo la colaboración, es usar la herramienta que tengas y a veces va a ser foto y a veces va a ser otro. Yo no tenía idea de que esto iba a terminar siendo un libro, por ejemplo, y no fantaseaba con eso, se fue dando porque realmente me pareció que era el formato más adecuado. Además, creo que lo colaborativo es hiper agotador realmente, pero me sigue pareciendo el camino más interesante porque estás en conflicto todo el rato. El conflicto es lo que te hace crecer a nivel personal y volverte a poner en tu lugar y decir ¡uy! aquí no estamos de acuerdo y decir ok, cómo le hacemos para seguir dándonos la mano. Creo que todo eso te va alejando de los discursos maniqueístas: blanco o negro, bueno o malo, y te vas dando cuenta de que todo es mucho más complejo y por lo tanto eso lo hace mucho más real.

Personalmente y como mexicana, tengo una fuerte conexión con la comida. Cuando hablo con mexicanos que también viven en Nueva York, una de las primeras preguntas que nos hacemos es ¿Qué es lo primero que comerás cuando regreses a México? ¿Crees que a través de la cocina, pueda haber una mayor consciencia sobre el problema de la desaparición forzada?

En los años 60 se puso muy de moda en Latinoamérica la desaparición forzada pero desde el Estado como fuerza dictatorial. En el caso de México es muy curioso porque la desaparición forzada en masa se da en democracia, se da en un “Estado de Derecho”. Obviamente entre muchas comillas porque la metodología sigue siendo la misma. Mucha gente que es parte de los grandes grupos de narcos, armados eran militares. Hay una formación que viene del mismo lugar aunque se esté aplicando desde otro espacio. Igualmente en Argentina cuando desaparecían a la gente está ese gran discurso de “no pues algo habrá hecho” y ahí viene toda la estigmatización que es una de las cosas que hay que combatir. Hay que combatir la desaparición forzada pero eso no está en nuestras manos tan claramente, lo que sí está es combatir la estigmatización de la gente que desaparecen y de los familiares que los buscan porque se va des-construyendo el tejido social y entonces ya no hay una sociedad fuerte. Para mi una de las herramientas, como artistas, fotógrafos, da igual, es pensar realmente qué quieres, qué quieres aportar, qué quieres hacer, cómo puedes apoyar y al final son granitos de arena. También desde el lado positivo, cuando yo conozco a todos estos grupos de mujeres, ya sea forenses o que sean grupos de búsqueda, hay una red de resistencia brutal y tampoco hay que olvidarlo, que no son sólo víctimas, son una red. Mirna conoce al equipo forense Argentino y a otros equipos forenses y eso se va creando también y hay que poner luz en eso pues porque es un trabajo interesante. Cuando estaba hablando con las señoras de Atacama, no tenían la menor idea de la cuestión de desaparición en México y las señoras en México no tenían idea de que en Chile o en Argentina había señoras que habían estado buscando entonces creo que justo nuestro lugar es poder facilitar esta vinculación porque quiere decir que no están solas y eso da mucha fuerza.

Pie de foto

Herramientas de trabajo del EAAF, Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense- 2017

Miércoles de rastreo para las Rastreadoras de el Fuerte. Los Mochis, Sinaloa, 2017

Huecos de palas y restos de ropa encontrados en un día de rastreo. Los Mochis, Sinaloa, 2018

Sonia Chanes, cocina en su casa, la capirotada, el plato preferido de su hijo Pablo Dean que fue desaparecido el 10 de mayo de 2018. Sonia lo buscó y lo localizó el 4 de diciembre de 2019

Los chiles chiltepines de Manky. Maria Cleofas Lugo busca a su hijo Juan Francisco, fue desaparecido el 19 de Junio de 2015. Manky lo sigue buscando.

Craneo oseo de hombre encontrado en la región de Tucumán por el EAAF. Argentina, 2017

Correspondencia de paisaje, entre un resto óseo y una vista aérea donde se encontró, Argentina, 2017

Rastreo. Los Mochis Sinaloa, 2019